Post by Dracula on Nov 4, 2018 13:23:55 GMT -5

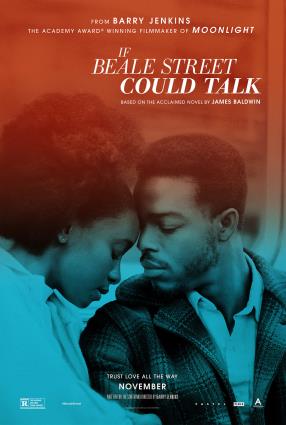

If Beale Street Could Talk(10/27/2018)

The great writer James Baldwin died about thirty years ago but it’s not hard to see that here in the late 2010s the guy is having a bit of “a moment.” I think this started with the rise of Ta-Nehisi Coates as a thinker and public intellectual. Coates, with his intellectual demeanor, roots in the literary world, and uncompromising politics in many ways felt like Baldwin’s intellectual descendant and he more or less invited the comparisons when he wrote his 2015 essay collection “Between the World and Me” as a letter to his teenage son, a literary device that was not dissimilar from one that Baldwin used in his 1963 book “The Fire Next Time.” Baldwin’s next re-emergence happened with the release of Raoul Peck’s documentary “I Am Not Your Negro,” which was adapted from Baldwin’s final manuscript and looked at his views of the civil rights movement and of larger American culture. That was a great documentary but it was a limited one insomuch as it was largely concerned with Baldwin’s work as an essayist and as a public intellectual and was not really focusing on his work as a novelist, which is what made him famous in the first place. Enter Barry Jenkins, red hot from his amazing Oscar winning film Moonlight, who has decided to bring attention to that said of Baldwin’s career by making as his next film an adaptation of Bladwin’s 1974 novel “If Beale Street Could Talk.”

Despite the tile the film actually isn’t set in Memphis and is instead set in Harlem during the early 70s. The film is told from the perspective of Clementine “Tish” Rivers (KiKi Layne), a nineteen year old who has fallen deeply in love with her longtime friend Alonzo “Fonny” Hunt (Stephan James). Unfortunately, as the movie begins Fonny is in Rikers Island awaiting trial for an alleged rape, one that Tish knows he didn’t commit because she was with him when it was alleged to have happened, an alibi the police do not believe because of her relationship to Fonny. Complicating matters further, Tish is apparently pregnant with Fonny’s baby. From here we get a number of flashbacks about Tish and Fonny’s courtship and attempts at building a life interspersed with material about the family’s attempts to find a way to help get him out of jail.

“If Beale Street Could Talk” was not one of James Baldwin’s more famous novels either in its day or in modern times before Barry Jenkins decided to adapt it. It was written after Baldwin was at the height of his fame and at a time when America was a bit weary of the topic of race, believing falsely that the Civil Rights Movement had already accomplished everything that needed to be accomplished and that everything else would just sort itself out eventually. Baldwin’s novel certainly doesn’t labor under any delusions that that is true but it’s not a book about the macro-politics of civil rights so much as a portrait of the small and not so small indignities that interrupt black life and prevent greater prosperity for the African American family. In particular the story looks at the effects of the criminal justice system on black life, which I think is a big part of why Jenkins believed the film would be particularly relevant today. The story is very much designed to make you root for the couple at the center of it and to be extremely frustrated by the fact that they’re being kept apart by circumstance. In this sense the film is a very traditional romance plot, but one where society is keeping its characters apart rather than parents or misunderstandings within the relationship.

As a case study in the criminal justice system Fonny’s is perhaps an extreme case as it seems that the police involved have gone through a lot of trouble to frame him for a fairly serious crime for rather petty reasons, something that is probably not unprecedented in the history of American policing but which remains a something of a worst case scenario. Another character played by Brian Tyree Henry comes into the film at a certain point and tells a story about getting a rather brutal prison sentence for carrying weed on his person, which is probably a bit more representative of the kind of cases that are overfilling American prisons in a post-“War on Drugs” era than Fonny’s predicament. There is also, in this climate, something just a little queasy about having a film center around trying to get a rape victim to recant her accusation even if that accusation appears to have been influenced by biased police officers, but the film does manage to portray that woman’s story with sensitivity as well. Still, the bigger point here is about how disruptive arrests like this are on the black family and the ways in which they cannot count on a fair trial or treatment.

Really though, the story’s relevance to modern political debates are not what makes this movie special, what really stands out is simply how well it renders the lives of its characters. The film certainly brings early 70s New York to life in an interesting way, endowing it with some of the romance of something like Manhattan when necessary while also showing some of the grit and hardship that living there could entail. The movie doesn’t shy away from the fact that it’s set during a particular period, the characters seem to have appropriate hairstyles and have a habit of referring to people as “cats,” but it avoids emphasizing the kitchier elements of that decade. Most of the music the characters listen to seems to be the jazz and blues of an earlier time rather than the chart hits of 1973 and the movie doesn’t give anyone an oversized afro or anything. In general the movie uses a lot of the same cinematic tricks that made Moonlight such a revelation but applies them to what is structurally a very different movie that operates in very different ways. Jenkins and cinematographer James Laxton have once again managed to create the perfect color scheme for the film and Nicholas Britell has contributed another fine score for this film, and the cast is absolutely killer. KiKi Layne, who as far as I can tell from IMDB has done almost nothing onscreen except for a couple of guest starring roles on TV, manages to anchor the film perfectly and Stephan James brings just the right mix of sensitivity and masculinity to Fonny. Regina King is also a standout as Tish’s mother, who comes to have a key sequence late in the film.

In terms of adaption the book skews very close to Bladwin’s novel, to the point where it acts as an almost word for word adaptation at times, which mostly works for the movie as it encourages Jenkins to leave in little bits of character that other movies might have cut out as superfluous. Little bits like Tish’s discomfort with her job at a department story perfume counter add a lot to the movie and easily could have been left out of a screenplay that were less reverent to the adaptation source, but this reverence can be a bit of a hindrance as well. For instance there is a lengthy scene at the beginning of the book and movie in which Tish’s family is at odds with Fonny’s self-righteous mother, which is in and of itself an excellent scene, but the conflict it establishes basically never comes up again in the movie and it feels like a bit of a dangling thread at the end. That and another subplot about the two lovers’ fathers conspiring to raise funds for Fonny’s defense are both left unresolved in the movie, in part because of the one aspect of the novel that Jenkins chose to alter in a significant way: its ending. I will not go into detail about this except to say that the ending of the novel is a bit abrupt and probably did need a change of some kind, his solution is to omit some of the material that would have slightly resolved the above plot threads in favor of an epilog he’s added which I don’t think fits exactly with what the rest of the film is setting up.

That was kind of an odd decision but I see what Jenkins was going for and aside from that one misstep I think this is basically another triumph for Jenkins. I’m not sure whether or not I’d consider this to be the better movie than Moonlight, truth be told they aren’t as easy to compare side to side as you would think given that they were more or less made by the same filmmaking team. If Beale Street Could Talk’s literary nature and general talkativeness differentiate it from Moonlight’s unique triptych narrative and enigmatic lead character, but what the two movies have in common is that they are both trying to apply a level of artistry to stories that the cinema and culture as a whole often renders as sensationalistic stereotypes. In the eyes of society Moonlight’s Chiron is merely a drug dealer, but Jenkins managed to show him as a lot more than that, and he is similarly able to show through this movie that Tish is far more than a mere “baby mama” and he effectively both explains why her life is the way it is while also endowing it with a clear degree of dignity. By the film’s end you feel like you’ve made a connection with its characters and that you’ve gone on something of a journey with them, which is theoretically what all movies are supposed to do but it’s kind of rare for one to really deliver on that and this one does.

****1/2 out of Five

The great writer James Baldwin died about thirty years ago but it’s not hard to see that here in the late 2010s the guy is having a bit of “a moment.” I think this started with the rise of Ta-Nehisi Coates as a thinker and public intellectual. Coates, with his intellectual demeanor, roots in the literary world, and uncompromising politics in many ways felt like Baldwin’s intellectual descendant and he more or less invited the comparisons when he wrote his 2015 essay collection “Between the World and Me” as a letter to his teenage son, a literary device that was not dissimilar from one that Baldwin used in his 1963 book “The Fire Next Time.” Baldwin’s next re-emergence happened with the release of Raoul Peck’s documentary “I Am Not Your Negro,” which was adapted from Baldwin’s final manuscript and looked at his views of the civil rights movement and of larger American culture. That was a great documentary but it was a limited one insomuch as it was largely concerned with Baldwin’s work as an essayist and as a public intellectual and was not really focusing on his work as a novelist, which is what made him famous in the first place. Enter Barry Jenkins, red hot from his amazing Oscar winning film Moonlight, who has decided to bring attention to that said of Baldwin’s career by making as his next film an adaptation of Bladwin’s 1974 novel “If Beale Street Could Talk.”

Despite the tile the film actually isn’t set in Memphis and is instead set in Harlem during the early 70s. The film is told from the perspective of Clementine “Tish” Rivers (KiKi Layne), a nineteen year old who has fallen deeply in love with her longtime friend Alonzo “Fonny” Hunt (Stephan James). Unfortunately, as the movie begins Fonny is in Rikers Island awaiting trial for an alleged rape, one that Tish knows he didn’t commit because she was with him when it was alleged to have happened, an alibi the police do not believe because of her relationship to Fonny. Complicating matters further, Tish is apparently pregnant with Fonny’s baby. From here we get a number of flashbacks about Tish and Fonny’s courtship and attempts at building a life interspersed with material about the family’s attempts to find a way to help get him out of jail.

“If Beale Street Could Talk” was not one of James Baldwin’s more famous novels either in its day or in modern times before Barry Jenkins decided to adapt it. It was written after Baldwin was at the height of his fame and at a time when America was a bit weary of the topic of race, believing falsely that the Civil Rights Movement had already accomplished everything that needed to be accomplished and that everything else would just sort itself out eventually. Baldwin’s novel certainly doesn’t labor under any delusions that that is true but it’s not a book about the macro-politics of civil rights so much as a portrait of the small and not so small indignities that interrupt black life and prevent greater prosperity for the African American family. In particular the story looks at the effects of the criminal justice system on black life, which I think is a big part of why Jenkins believed the film would be particularly relevant today. The story is very much designed to make you root for the couple at the center of it and to be extremely frustrated by the fact that they’re being kept apart by circumstance. In this sense the film is a very traditional romance plot, but one where society is keeping its characters apart rather than parents or misunderstandings within the relationship.

As a case study in the criminal justice system Fonny’s is perhaps an extreme case as it seems that the police involved have gone through a lot of trouble to frame him for a fairly serious crime for rather petty reasons, something that is probably not unprecedented in the history of American policing but which remains a something of a worst case scenario. Another character played by Brian Tyree Henry comes into the film at a certain point and tells a story about getting a rather brutal prison sentence for carrying weed on his person, which is probably a bit more representative of the kind of cases that are overfilling American prisons in a post-“War on Drugs” era than Fonny’s predicament. There is also, in this climate, something just a little queasy about having a film center around trying to get a rape victim to recant her accusation even if that accusation appears to have been influenced by biased police officers, but the film does manage to portray that woman’s story with sensitivity as well. Still, the bigger point here is about how disruptive arrests like this are on the black family and the ways in which they cannot count on a fair trial or treatment.

Really though, the story’s relevance to modern political debates are not what makes this movie special, what really stands out is simply how well it renders the lives of its characters. The film certainly brings early 70s New York to life in an interesting way, endowing it with some of the romance of something like Manhattan when necessary while also showing some of the grit and hardship that living there could entail. The movie doesn’t shy away from the fact that it’s set during a particular period, the characters seem to have appropriate hairstyles and have a habit of referring to people as “cats,” but it avoids emphasizing the kitchier elements of that decade. Most of the music the characters listen to seems to be the jazz and blues of an earlier time rather than the chart hits of 1973 and the movie doesn’t give anyone an oversized afro or anything. In general the movie uses a lot of the same cinematic tricks that made Moonlight such a revelation but applies them to what is structurally a very different movie that operates in very different ways. Jenkins and cinematographer James Laxton have once again managed to create the perfect color scheme for the film and Nicholas Britell has contributed another fine score for this film, and the cast is absolutely killer. KiKi Layne, who as far as I can tell from IMDB has done almost nothing onscreen except for a couple of guest starring roles on TV, manages to anchor the film perfectly and Stephan James brings just the right mix of sensitivity and masculinity to Fonny. Regina King is also a standout as Tish’s mother, who comes to have a key sequence late in the film.

In terms of adaption the book skews very close to Bladwin’s novel, to the point where it acts as an almost word for word adaptation at times, which mostly works for the movie as it encourages Jenkins to leave in little bits of character that other movies might have cut out as superfluous. Little bits like Tish’s discomfort with her job at a department story perfume counter add a lot to the movie and easily could have been left out of a screenplay that were less reverent to the adaptation source, but this reverence can be a bit of a hindrance as well. For instance there is a lengthy scene at the beginning of the book and movie in which Tish’s family is at odds with Fonny’s self-righteous mother, which is in and of itself an excellent scene, but the conflict it establishes basically never comes up again in the movie and it feels like a bit of a dangling thread at the end. That and another subplot about the two lovers’ fathers conspiring to raise funds for Fonny’s defense are both left unresolved in the movie, in part because of the one aspect of the novel that Jenkins chose to alter in a significant way: its ending. I will not go into detail about this except to say that the ending of the novel is a bit abrupt and probably did need a change of some kind, his solution is to omit some of the material that would have slightly resolved the above plot threads in favor of an epilog he’s added which I don’t think fits exactly with what the rest of the film is setting up.

That was kind of an odd decision but I see what Jenkins was going for and aside from that one misstep I think this is basically another triumph for Jenkins. I’m not sure whether or not I’d consider this to be the better movie than Moonlight, truth be told they aren’t as easy to compare side to side as you would think given that they were more or less made by the same filmmaking team. If Beale Street Could Talk’s literary nature and general talkativeness differentiate it from Moonlight’s unique triptych narrative and enigmatic lead character, but what the two movies have in common is that they are both trying to apply a level of artistry to stories that the cinema and culture as a whole often renders as sensationalistic stereotypes. In the eyes of society Moonlight’s Chiron is merely a drug dealer, but Jenkins managed to show him as a lot more than that, and he is similarly able to show through this movie that Tish is far more than a mere “baby mama” and he effectively both explains why her life is the way it is while also endowing it with a clear degree of dignity. By the film’s end you feel like you’ve made a connection with its characters and that you’ve gone on something of a journey with them, which is theoretically what all movies are supposed to do but it’s kind of rare for one to really deliver on that and this one does.

****1/2 out of Five